If These Walls Could Rock

History

50 Years and Counting at the Sunset Marquis

Celebrating 50 years with a fab new face-lift, the Sunset Marquis remains a rock ‘n’ roll legend. In an exclusive excerpt from their new book, “If These Walls Could Rock,” Mark A. Rosenthal and Craig A. Williams explain why the hotel is still the coolest spot in LA.

In the summer of 1961, real estate developer George Rosenthal sat in the living room of Chicago’s Playboy mansion with Hugh Hefner trying to decide whether or not they should take a $12 million loan from Jimmy Hoffa.

On the upside, it was the amount of money Rosenthal needed to build a new Playboy Club and hotel in the heart of West Hollywood’s legendary Sunset Strip. The downside was that getting into business with Jimmy Hoffa presented the very real potential of being hazardous to your health. And it didn’t help that Robert Kennedy, the newly appointed US attorney general, had an almost singular determination to bring Hoffa down. To take money from the Teamsters union boss was also to draw the attention, if not the ire, of the new attorney general. Hefner, who was already scrambling to stay a step ahead of the postmaster general, the House Un-American Activities Committee, and the religious right for “the smut and pornography” he was peddling, simply didn’t need the additional attention.

“If we take this money,

you’re gonna get back to your office in LA and you know who’s going to pop out of the bottom drawer of your desk?”

Hefner asked. “Who?”

“Bobby Kennedy.”

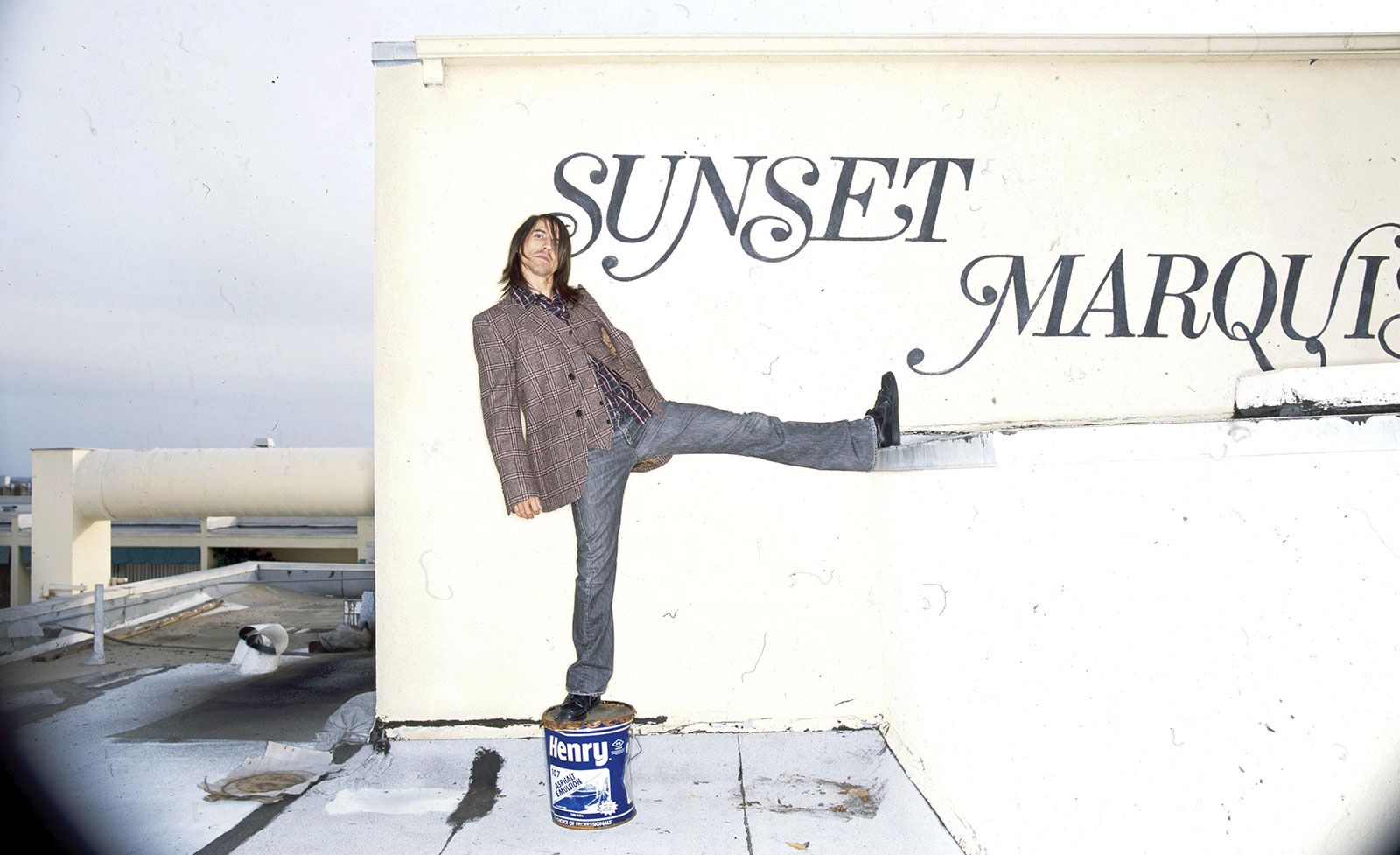

“Sunset Marquis”

He called the place The Sunset Marquis

after his newly born son Markey

But watching nubile Playboy bunnies slide down a fire pole through a hole in the floor of the mansion’s living room and into an underground pool-cum-bar known as “The Grotto,” then 29-year-old Rosenthal knew one thing for certain: “There was no way I wasn’t going to build a Playboy Club in LA.”

After turning down Hoffa’s proposal, Rosenthal was able to find local financing for the Playboy office building (which would house the club), but not the Playboy hotel. Shortly after construction began on the office building and club, and still sensing the need for accommodations for the performers and guests at the club, he purchased property just down the street at 1200 Alta Loma Drive.

He called the place The Sunset Marquis after his newly born son Markey, and for the past 50 years, it has been the home away from home for actors, comedians, writers, artists, filmmakers, fashion designers, supermodels, restaurateurs, billionaire entrepreneurs, and the newest breed of entertainer when the hotel opened its doors in 1963: rock stars.

The stories of the Sunset Marquis and the history of rock ’n’ roll are inextricably intertwined. Set just off the Sunset Strip, home to several of the first rock clubs in the world, the Marquis became a safe haven for those in the know to escape the chaos of the surrounding jungle. At the corner of Sunset and San Vicente, the Whisky a Go Go opened in January of 1964 as a venue for local bands like The Byrds and The Doors. The Whisky also witnessed the American debuts of British acts, including The Who, The Kinks, and Led Zeppelin.

Initially, these touring bands stayed at the Hyatt House, just east of the Marquis. While the “The Riot House,” as it came to be known, had Keith Moon driving motorcycles through the lobby and trays of food jettisoned from windows onto cop cars below, the Marquis was where the more established performers stayed while their roadies and groupies blew things up at the Hyatt.

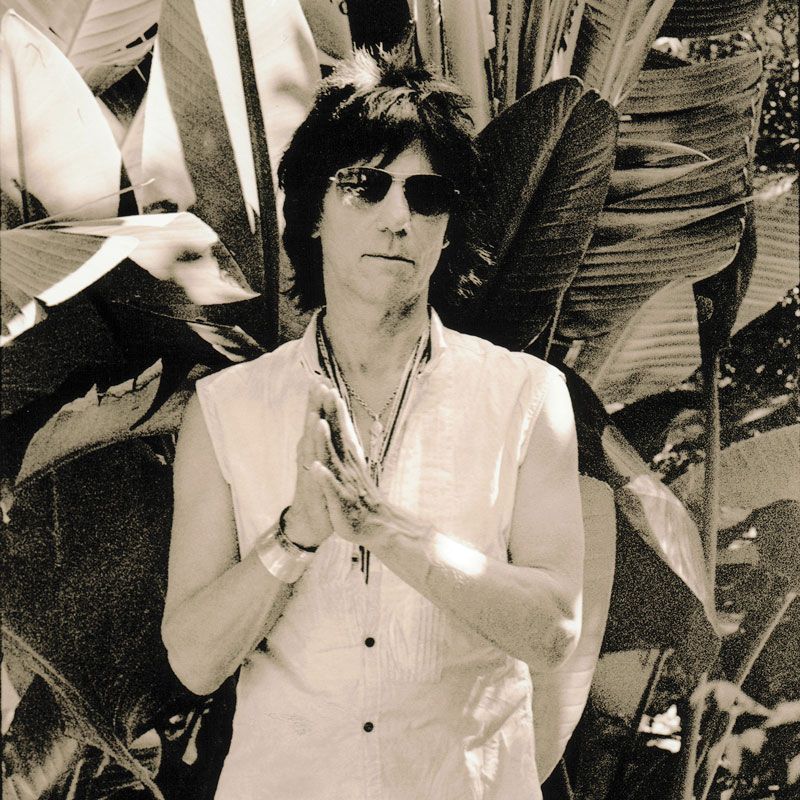

“I didn’t really like being breathed on,”

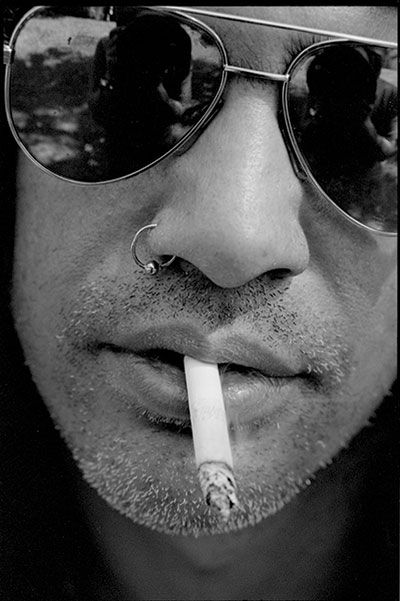

Marquis stalwart Jeff Beck says. “And when you wanted to get away from groupies, you had to get away. They couldn’t conceive that everybody moved down the street to the Marquis.”

Photo – Ross Halfin

“1970s – 1990s”

a party around the pool and later on in The Whiskey Bar

Says Rosenthal: “It became a party around the central pool with a lot of intellectual rat-a-tat. We also had a lot of divorced Hollywood writers who began living at the hotel. Jackie Gayle used to joke that there was a great view of the Hollywood Hills from the pool. Unfortunately, it was of the homes that the wives got in their divorces.”

In the 1970s the Troubadour was home to multi-night stints by emerging acts like Neil Diamond—who used to perform by the Sunset Marquis pool to pay his tab—Elton John—still frequently seen eating in the restaurant or on his way to the recording studio—and Bruce Springsteen, who still stays at the hotel. The Sunset Marquis was home to Bob Marley and The Wailers during their now-legendary shows at The Roxy. Later in the ’70s, the Marquis was home to punk and new wave bands—The Clash, Blondie, The Runaways, and the Ramones. “Back in the day they let me park my bus on-site, which is bloody amazing in a cosmopolitan, busy city, so after driving an all-nighter, I could sleep in, then stagger to my room without tripping over anyone,” reminisces David Coverdale.

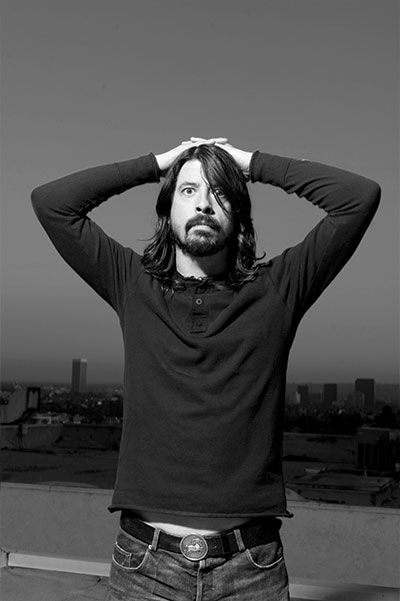

The hotel became ground zero for the metal scene in the neon 1980s (bands such as Metallica, Iron Maiden, Kiss, Guns ‘N Roses, Aerosmith, and the Chili Peppers were guests), but remained home to mega stars like Phil Collins, Sting, and Julio Iglesias, as well. In the 1990s musicians like Dave Grohl of the Foo Fighters, Green Day, Usher, and Kings of Leon found their way to Alta Loma Drive. The Marquis was even home to an affair between Trent Reznor and Courtney Love, whose band, Hole, recorded the song “Sunset Marquis,” about her time at the hotel.

Also during the 1990s, the bar at the Marquis placed the hotel—uncomfortably at times—in the spotlight. The room was a converted office with a capacity of a little more than 60 regular people but could fit up to 82 supermodels, and it did. Walking into The Whiskey Bar, as it was named (Rande Gerber was hired as a consultant after the success of his Whiskey Bars in New York), was like walking into George Michael’s “Freedom” video while thumbing through The Victoria’s Secret catalog. Lines wrapped up Alta Loma and around Sunset Boulevard. Groupies scaled walls in mini-skirts and pumps. One poor girl, unfortunately, landed on the porch of James Brown’s villa only to find herself surrounded by The Godfather of Soul’s well-strapped security detail.

“It was everything you’d ever dreamed,”

“the heyday of rock’n’roll”

Sunset Strip and Hollywood and rock ’n’ roll wrapped into one

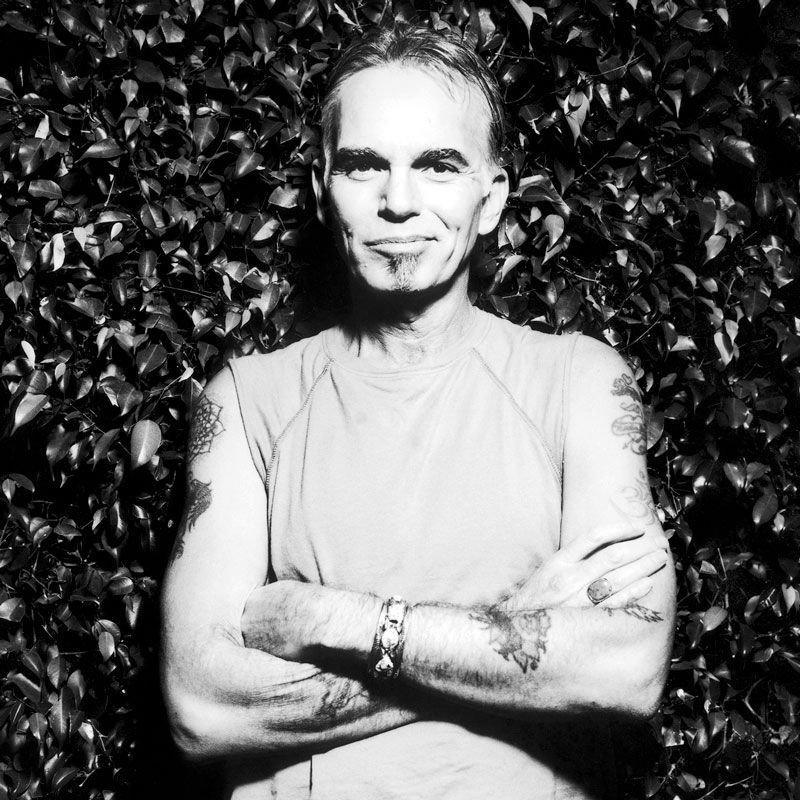

On the upside, stars like George Clooney, Owen Wilson, Jennifer Aniston, and Billy Bob Thornton became regulars. “It was everything you’d ever dreamed,” Thornton says. “It was like they built this place specifically so if you wanted to live the life you read about in the books, this is where you’d come and do it.” But the downside was that it threatened what had always made the Marquis so special. “It created problems with some of our big clients in the beginning,” one former executive says. “They came to the Sunset to get away from all the riffraff, hangers-on, and groupies, and that’s who that bar attracted in the beginning.”

“This is as close as it gets to the heyday of rock ’n’ roll, where you could have a community of other artists that you hung out with,” counters Thornton. “This still embodies the days of the Sunset Strip and Hollywood and rock ’n’ roll and all of it wrapped into one. The times we had in the Whiskey Bar were… it felt so historic. You felt like some day they were going to write a book about it. And sure enough…” Later, in 2005, the bar was renamed Bar 1200 and managed to recapture a good part of its quaint glory.

“I just fucking love this place!”

“continues to prosper”

full-service hotel, restaurant, spa and recording studio

Today, the Sunset Marquis has grown into a full-service hotel with 152 suites and villas, a restaurant, spa, and a recording studio where dozens of Grammy Award-winning records have been produced. The hotel’s main building has recently undergone a face-lift that completes a $35 million renovation and expansion (helmed by interior designer Oliva Villaluz) that began in 2004, and even includes parking for two tour buses. Now spread out over four acres, the Marquis, with the seclusion it offers, continues to attract new stars like Kristen Stewart, Robert Pattinson, and various American Idol winners, while maintaining the affections of those who created the legends here, including Steven Tyler and Gene Hackman, who has been bringing his family to the hotel since its doors opened in 1963. In a city where few careers last more than 15 minutes, that the Marquis has prospered over five decades is remarkable. And that’s exactly how George Rosenthal planned it.

“I always had the vision

that if there was some way in which I could emulate the Garden of Allah’s ambiance, I wanted to do that,”

“garden of allah”

George Rosenthal’s model for what

he thought a hotel should be

The Garden of Allah was a West Hollywood mansion-turned-apartment house owned by silent film star Alla Nazimova. From the late 1920s until Nazimova’s death in 1945, it was at various times home to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Cole Porter, the Marx Brothers, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Marlene Dietrich, Orson Welles, Buster Keaton, Ernest Hemingway, Errol Flynn, Greta Garbo, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and the women who would become Rudolph Valentino’s ex-wives once they left him for the openly lesbian Nazimova. The place was, for the film icons who stayed there, their conception of paradise.

Although the Garden of Allah was demolished in 1959, it was not forgotten. When George Rosenthal was looking to build his hotel in the early 1960s, the Garden of Allah was his model for what he thought a hotel should be. And he doesn’t mean the bougainvillea.

“They smoked a lot more dope there than they did anyplace else,” Rosenthal says. “It was that no-holds-barred kind of thing where everyone who’s there is a part of this family, like the early writers’ salons in France. I met a bunch of artists in Paris and they were really freewheeling and that’s how I wanted the Marquis to be. I hear that’s what it’s become,” he laughs. “I hope it’s become that!”